So, let's review our discussion of genre and film noir. We learned that genre's often develop in certain stages: primitive, classical, revisionist, and parodic.

Film noir drew from pulp fiction, gangster films, and German Expressionism in the establishment of its conventions. The films often included archetypal characters like the persistent male hero and the dangerous spider-woman. The stories were set in big cities and often represented violent crimes (in an amoral way). The use of highly-stylized design and archetypal characters (like in Expressionism) was used to illustrate the anxieties felt by American society. The horrors of war, poverty and industrialization seemed to introduce an existential crisis that was addressed in film noir.

Primitive Manifestations of the Western

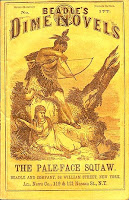

So, a good while before the invention of film technology, the western genre was created. Literature like James Fenimore Cooper's "Leatherstocking Tales" and the more cheaply-produced dime novels were popular in the early 19th century. Westward expansion was a reality: pioneers were trekking across the country, conflicts among American settlers and Native American communities were occurring, and new territories were being claimed by the United States. These events made their way onto the pages of novels for the entertainment of readers who fascinated with the frontier adventure (but not typically experiencing it as reality).

So, a good while before the invention of film technology, the western genre was created. Literature like James Fenimore Cooper's "Leatherstocking Tales" and the more cheaply-produced dime novels were popular in the early 19th century. Westward expansion was a reality: pioneers were trekking across the country, conflicts among American settlers and Native American communities were occurring, and new territories were being claimed by the United States. These events made their way onto the pages of novels for the entertainment of readers who fascinated with the frontier adventure (but not typically experiencing it as reality).When film technology was developed in the late 19th century, the subjects of the western were among the first to be documented on the motion picture. Thomas Edison's "Buffalo Dance" is a good example of an early 'spectacle' film (remember the cats boxing) that uses a Native American custom (a familiar subject in westerns) to entertain its audience. Sound has been added to this clip, but the original would have been silent.

Among the first narrative films (films that told a story--as opposed to the 'actuality' films that simply documented day-to-day events), there were the origins of the the western film. Watch how Edison's "Cripple Creek Barroom" seems to foreshadow some common conventions in the classical western.

Edwin S. Porter's The Great Train Robbery expanded upon these early narrative shorts, by including multiple scenes and using new editing techniques like cross-cutting (to demonstrate the simultaneous occurrence of multiple events or to encourage association between two shots). Again, many of the conventions of the western can be identified in the film in their early forms.

The Classical Western Film

While the classical western's official beginning is ambiguous (some argue for Porter and others will delay the beginning until D.W. Griffith's films or even until the development of sound technology) I would say that director John Ford established the western as a film genre. His earliest films, during the silent period, are stories set in the west. He is responsible for the stardom of Western icons John Wayne and Henry Fonda. And during his career, he directed such hugely successful westerns like Stagecoach (1939), My Darling Clementine (1946), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), Rio Grande (1950), The Searchers (1956), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). While John Ford is the only film director who was influential in shaping the western (directors like Howard Hawks, William Wyler, George Stevens, Fred Zinneman, and others made valuable contributions as well), his overwhelming presence in the genre cannot be denied.

While the classical western's official beginning is ambiguous (some argue for Porter and others will delay the beginning until D.W. Griffith's films or even until the development of sound technology) I would say that director John Ford established the western as a film genre. His earliest films, during the silent period, are stories set in the west. He is responsible for the stardom of Western icons John Wayne and Henry Fonda. And during his career, he directed such hugely successful westerns like Stagecoach (1939), My Darling Clementine (1946), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), Rio Grande (1950), The Searchers (1956), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). While John Ford is the only film director who was influential in shaping the western (directors like Howard Hawks, William Wyler, George Stevens, Fred Zinneman, and others made valuable contributions as well), his overwhelming presence in the genre cannot be denied. The classical western film was set on the frontier. In the assigned chapter for this week, Belton discusses how the situation of the western on this border (much like the film noir's border setting) encourages narrative and thematic emphases on binary opposition. So, at the heart of the relationship between characters in the films is a conflict between the east and west, civilization and wilderness, fact and fiction, culture and nature, community and individual, man and woman. The frontier was the point of intersection between these polar opposites, and it was the place in which the east, the civilized, the cultured, the communal, the masculine must overcome that opposition. So, while the western film showed the inherent conflict in westward expansion, it emphasizes the overcoming of this conflict and champions the idea of manifest destiny.

The classical western film was set on the frontier. In the assigned chapter for this week, Belton discusses how the situation of the western on this border (much like the film noir's border setting) encourages narrative and thematic emphases on binary opposition. So, at the heart of the relationship between characters in the films is a conflict between the east and west, civilization and wilderness, fact and fiction, culture and nature, community and individual, man and woman. The frontier was the point of intersection between these polar opposites, and it was the place in which the east, the civilized, the cultured, the communal, the masculine must overcome that opposition. So, while the western film showed the inherent conflict in westward expansion, it emphasizes the overcoming of this conflict and champions the idea of manifest destiny. This formula of binary opposition is seen in the genre's archetypal characters. The division between masculinity and femininity is super-emphasized in these films. I think the characters (or character, you could argue) John Wayne is the personification of the western's idea of masculinity: He's a cowboy. He is not very intelligent. He solves problem through physical conflict. When he is not enforcing the law, he is reaffirming the values of the old west. The western man shares some characteristics with the detective from film noir, but rather than disenchanted with the American institution, the western hero is a representative of it. When John Wayne isn't wearing a star, or a uniform, he wears the iconic cowboy costume, establishing himself as the personification of American ideals (patriotism, justice, imperialism, etc).

This formula of binary opposition is seen in the genre's archetypal characters. The division between masculinity and femininity is super-emphasized in these films. I think the characters (or character, you could argue) John Wayne is the personification of the western's idea of masculinity: He's a cowboy. He is not very intelligent. He solves problem through physical conflict. When he is not enforcing the law, he is reaffirming the values of the old west. The western man shares some characteristics with the detective from film noir, but rather than disenchanted with the American institution, the western hero is a representative of it. When John Wayne isn't wearing a star, or a uniform, he wears the iconic cowboy costume, establishing himself as the personification of American ideals (patriotism, justice, imperialism, etc). The women in the western are much like the women in film noir--they are divided into dual natures. Some of the female characters represent the dominated, colonized, civilized. They are much like film noir's "nurturing women", who are housewives and schoolteachers. They represent the success of America's civilization of the west. Other female characters, often represented as Native American or Mexican, often represent the challenge of American civilization. The characters are more powerful, sexualized, and exoticized, and they (like the land they inhabit and the communities they come from), must be properly civilized.

The women in the western are much like the women in film noir--they are divided into dual natures. Some of the female characters represent the dominated, colonized, civilized. They are much like film noir's "nurturing women", who are housewives and schoolteachers. They represent the success of America's civilization of the west. Other female characters, often represented as Native American or Mexican, often represent the challenge of American civilization. The characters are more powerful, sexualized, and exoticized, and they (like the land they inhabit and the communities they come from), must be properly civilized.You can see how the idea of the "taming of the west" is inherently connected with very particular definitions of proper masculinity and femininity and with the domination of men over women. It's no surprise then that the male characters are the protagonists in westerns, while the women either give support or pose a potential threat to the men.

In his book Sixguns and Society, theorist Will Wright breaks down the classic western film into sixteen 'narrative functions':

- The hero enters a social group.

- The hero is unknown to the social group.

- The hero is revealed to have an exceptional ability.

- The society recognizes a difference between themselves and the hero; the hero is given a special status.

- The society does not completely accept the hero.

- There is a conflict of interests between the villains and the society.

- the villains are stronger than the society; the society is weak.

- There is a strong friendship or respect between the hero and a villain.

- The villains threaten the society.

- The hero avoids involvement in the conflict.

- The villains endanger a friend of the hero.

- The hero fights the villains.

- The society is safe.

- The society accepts the hero.

- The hero loses or gives up his special status.

Questioning the Classical Western

Now, starting in around the 60's, the conventions of the western have been reevaluated. In 'spaghetti westerns', a revisionist revival of the genre in Italian cinema, the old west is perceived from an international perspective. And while the films maintain many of the genre's conventions, some really substantial questions are raised about some of the principles on which the genre is founded.

Here's the opening scene from the (freaking awesome) Sergio Leone film Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Check it out and see if you can identify any deviations from classical western convention.

Two of the men killed are played by western icons Woody Strode and Jack Elam. The classical characters are replaced by the new western hero. The new hero arrives by train, and the film's narrative emphasizes the violence and oppression that accompanied the building of the railroad. And finally, the main character, rather than be accompanied by a non-diagetic film score, plays his own theme music on his harmonica--a self-reflexive reference to both the awesomeness that is Ennio Morricone (the film's composer) and the prominence of musical accompaniment in the western film.

Other revisionist westerns like The Wild Bunch, Last of the Mohicans, Unforgiven, Dances with Wolves, Open Range, and Brokeback Mountain further question the ideological assumptions behind the classical genre. Cultural representations (of Mexicans and Native Americans, for example) are examined. Issues of violent oppression are addressed. And the definition of masculinity is reconsidered (especially in Brokeback Mountain).

Other revisionist westerns like The Wild Bunch, Last of the Mohicans, Unforgiven, Dances with Wolves, Open Range, and Brokeback Mountain further question the ideological assumptions behind the classical genre. Cultural representations (of Mexicans and Native Americans, for example) are examined. Issues of violent oppression are addressed. And the definition of masculinity is reconsidered (especially in Brokeback Mountain).The Final Frontier

And while people have repeatedly said for the last thirty years that the western film is dead, its elements have been appropriated by other genres. Many of the conventions of genre live on in historical epic films and war films (which we'll discuss next week). And perhaps more significantly, the western genre seems to have birthed the science-fiction film.

And while people have repeatedly said for the last thirty years that the western film is dead, its elements have been appropriated by other genres. Many of the conventions of genre live on in historical epic films and war films (which we'll discuss next week). And perhaps more significantly, the western genre seems to have birthed the science-fiction film.The western film's decline in popularity and the sci-fi film's growth popularity in the mid-20th century may have been due to the fact that west was already won. Then, with the Space Race, the next frontier was outer space, so the same conventions and values were transferred to a new narrative location. So, we have macho space-cowboys who combat alien races for control of land and power. (Consider Back to the Future III, Cowboy Bebop, Firefly, Toy Story, etc).

Consider this clip of our friend Han Solo, and see if you can see how the sci-film has adopted conventions of the western.

I think that it's interesting that in some recent sci-fi films, Earth has been the location of alien colonization. This premise situates the human population (often centering on the American people) as the colonized people (Mexican and Native Americans) of the classical western. Except in these films, the natives kick the settlers' butts.

And finally, some films parody the conventions of the western and sci-fi genres, further exposing some of the ideological contradictions found in the classic films. Here's a favorite of mine.

Mel Brooks' film Blazing Saddles addresses the racial stereotypes common to the western genre. And its great.

So What?

So, if the western is supposedly dead, why is this discussion important? Well, I think that our nation's identity is deeply rooted in the depictions of the west and the idealogical perspectives common to these depictions. Issues of gender and race, colonization and oppression are issues addressed in these films and issues that need to be addressed in our society today.

Assignment

Based on on our discussion of binary oppositions (like East/West, civilization/wilderness, etc) and your assigned readings, identify a text (novel, tv show, film, comic book, etc) that uses binary opposition to address an issue related to our studies. (Your text does not have to be a western, but it has to use binary opposition to an issue of race, class, gender, sexuality, etc). Discuss how the use of binary opposition may limit adequate understanding of the issue addressed. Be specific, using examples of plot, characters, and themes from the text (and what they indicate about the issue).

This is a heavier assignment, but you all have done well so far. Be particular about your choice of text. Think hard before you write. And be clear and specific in your writing. You'll do great.

Quiz

From Cooper Thompson's article, define homophobia and misogyny and discuss their relationship to traditional masculinity.